My third floor balcony overlooks a fish market. It’s nothing fancy, just a smattering of polythene paper stalls. The smell of fish sometimes is overwhelming, and the view is an eye-sore. But it’s the people in the market that are close to my heart. I like watching the vendors call out to their customers – each lady has a characteristic call – sometimes a whistle, a screech.

The most intense moments happen when the fishermen bring in their catch. This trade calls for a level of roughness, some bit of violence. A lot of the fishermen are usually tipsy, and will likely head back to the drinking dens after the sale.

Over time, I’ve noticed the rough, tipsy fishermen never sell all their catch. There’s always a bunch of fish sewn over their gills set aside from the sale. This is meant for their families. However carefree these men may appear to be, they always have their families in mind.

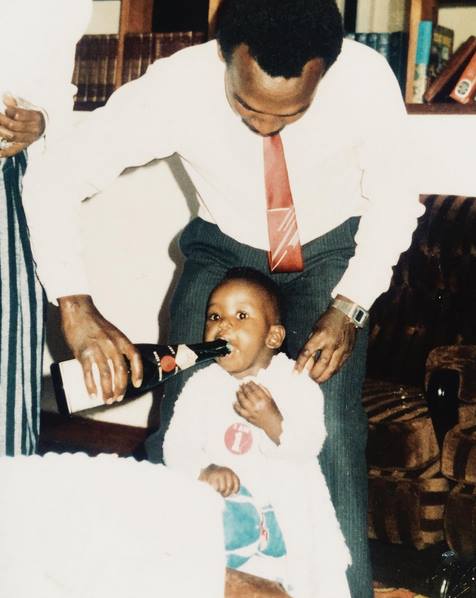

Their wives and kids come first.

This is what being a father means. From my balcony, I can see the pride and purpose in their steps as they first head home to deliver the daily bread, then stroll out for a stiff drink with their peers.

Back in the days, festive seasons would bring me a heavy cloud of sorrow. Christmas, Easter, occasional birthdays…name them all. I’d dread them. Because we always had to slaughter some animal. In the village, we’d be close to the animals we kept – and it’d take days before I got over it.

This ceremony was a masculine affair, and I still think of the chilly mornings. It was always early, before the children woke up. As the eldest son, sleeping in was a luxury. My father would rap on my door (my brothers and I lived in a separate house) – and whisper hoarsely:

“Ken! Ken! Go get the goat!”

I didn’t like it, but I’d jump out of bed. In those days, you’d be teased for days for a sign of weakness. In those days, it was deemed manly to show no fright at the sight of blood.

I’d grab the chosen goat and disappear into the semi-dark banana grove behind the main house. For a few minutes, I’d kneel with the goat’s head in my arms. I’d try to explain to the goat why it had to go down this way. I always felt like Judas Iscariot, with his 30 pieces of silver.

Shortly, father would appear with a knife and a small bucket. He’d wrestle the goat to the ground, and tie up his feet. He’d ask me to kneel on her back – to hold her down. Then, time would slow down…..

The overpowering smell of blood would hit me first. Then, the smell of sweat, and dung on father’s khaki overalls would join in. Nausea almost always overran me, and I would retch and vomit.

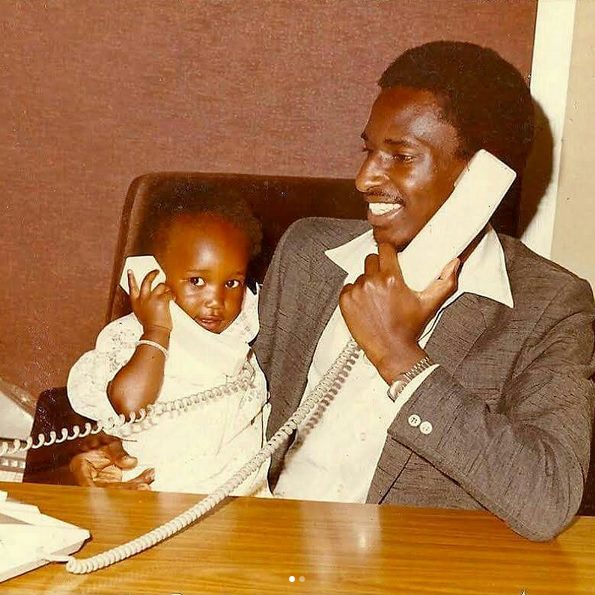

Father would look at me softly, and sometimes pat me on the head.

“Don’t worry, Ken. They die so that we may live”.

It’s been several decades, and these sacred memories never leave me. Memories of these solemn words, told over a bleeding goat.

Father is now retired, and no longer wrestles goats on festive days.

He now runs a butchery, albeit from home. He’d used a section of his pension, and I had acquired a Coop Bank loan – we jointly own this venture. His role is to source for live animals from the community – he’s gifted with amazing people skills. I take over from the slaughterhouse – distribution to various retail outlets and institutions, like hospitals and hotels.

It’s easy business, thanks to the New Co-op Internet Banking that allows me to manage my Co-op Bank account from one place. It allows real-time monitoring of payments to the butchery account through the Co-op Bank M-Pesa pay bill number 400200, and direct cash transfers via M-Coop Cash App.

I can also access banking features like statements, buying airtime and internet data direct from my account. The New Co-op Internet Banking allows convenient fund transfers to M-Pesa or any local bank account.

Towards dusk, I send the old man a message on his phone: Happy Father’s Day.

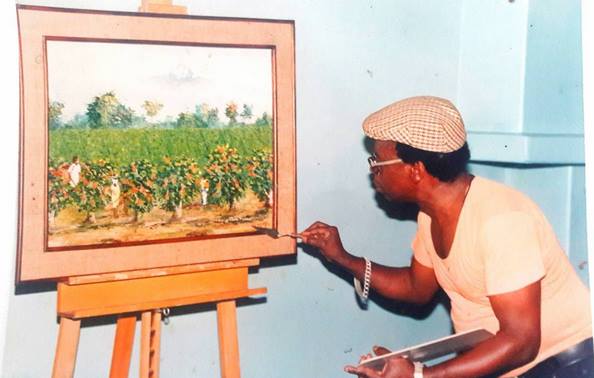

Fatherhood is a tricky responsibility and there’s no handbook, yet. A big part of who we are is a reflection of the fatherhood we grew up with…