A Ugandan town comes to terms with a massacre’s aftermath

Outside the mortuary in Kasese, grief-stricken families wait to find out if their missing relatives were among scores killed by Ugandan security forces at the weekend.

Huddling in groups, some pull clothes over their mouths and noses to mask the sickening stench of the decomposing corpses inside.

Kikanda Bwambale, 40, was back at the mortuary to look for his older brother, Siriro, after being turned away the previous day.

Bwambale last heard from Siriro on Saturday when he visited the local king’s palace to discuss a land issue. That day, clashes broke out between royal guards and Ugandan police that left nearly 90 dead.

“My brother had never been to the palace before. He was a peasant, he didn’t know anything about politics or the kingdom,” said Bwambale. “I think he’s been shot.”

Mumbere Isaac, 27, was also looking for his brother, Nyanza. “The bodies in there are burnt and decomposed,” he said, distraught that he may be unable to identify the corpse.

Sobs rang out as coffins were loaded into trucks or carried to grave sites as families who had recovered their dead began holding funerals.

The official police toll from weekend fighting first given on Sunday stands at 62. However Kasese’s district police commander has told AFP another 25 bodies were found in two sub-counties on Monday.

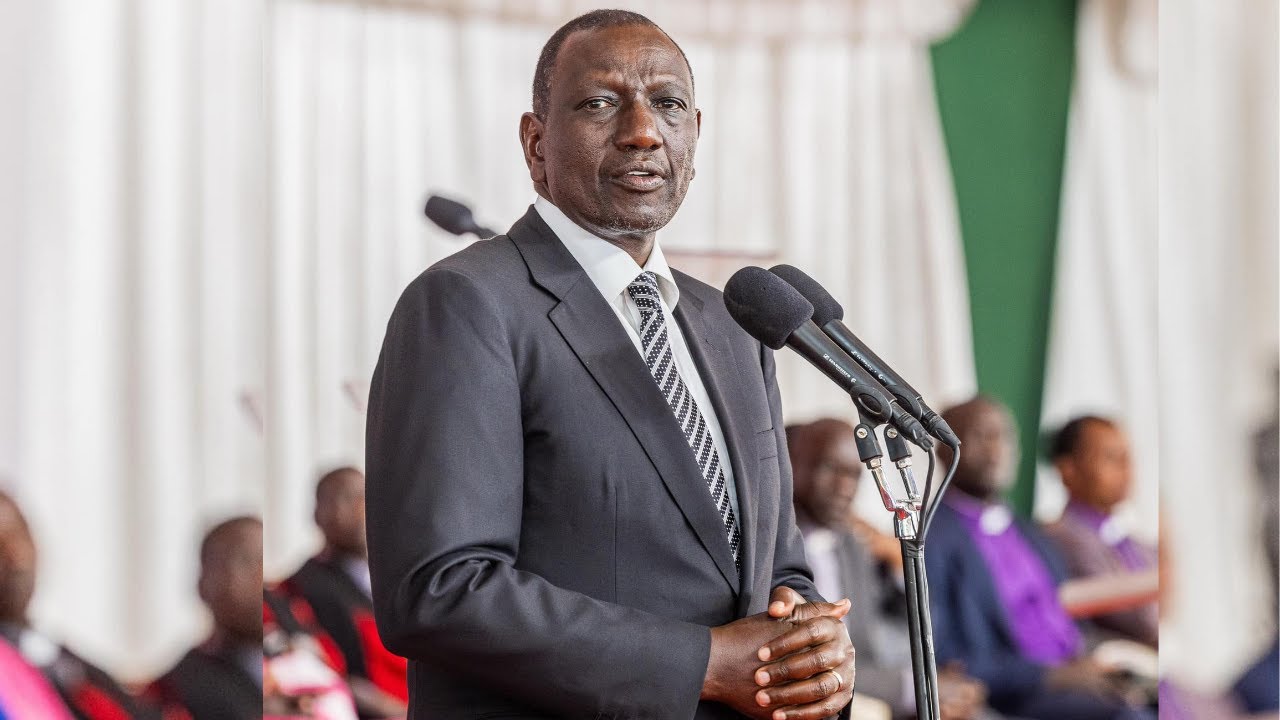

The government accused King Charles Wesley Mumbere of stoking a secessionist rebellion and stormed his palace on Sunday to arrest him. He was taken to the capital Kampala where he was charged with murder.

But in Kasese there are different stories, with some suspecting the real toll tops 100.

Tembo Jockim of the Ugandan Red Cross said many people remain missing.

“Civilians, wives to the royal guards were at the palace and we know that in the palace there were children and they’re seen neither in police custody nor in the death list,” Jockim said.

The Ugandan government alleges that kingdom hardliners want to secede and establish an independent state they call the Yiira Republic that would include a part of neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, whose people share the same culture and language as the local Bakonzo.

Before being recognised as a traditional kingdom in 2009, Rwenzururu had a long history as a separatist movement, and the government said a trained, armed militia had set up camp in the palace and surrounding Rwenzori mountains.

Uganda’s Internal Affairs Minister General Jeje Odongo said machine guns, machetes, spears and petrol bombs had been found in the palace.

But Bwambale said none of this meant anything to his missing brother.

“He didn’t support a Yiira Republic or not. He was not interested in that.”

Days after the violence, Kasese is gradually returning to a semblence of normality with shops and restaurants opening, but anguish and fear remain.

Near some market stalls in the town centre, Abdon — who did not want to give his full name for fear of reprisals — said the local ethnic group feels marginalised.

“The Bakonzo community feel that they have always been oppressed, even since colonial times. The whole of this region was underdeveloped,” he said.

But he denied government claims of ethnic militancy or a drive for secession.

“We’ve just heard of ‘Yiira’ on press or media but publicly nobody has held a rally or any gathering about that,” he said.

The kingdom’s prime minister Tembo Kitsumbwe disputes the official account that royal guards started the violence.

“I was inside my office at noon on Saturday when I received a call to say the office was being surrounded. I escaped through a side door and the Royal Guards closed the doors and refused to let the police and army enter,” he told AFP.

“Moments later the police just bombed the office. I ran to the palace and within an hour that was surrounded, too,” he said.

He called for the king to be released and for negotiations between the monarch and President Yoweri Museveni.

“If it’s a battle as they claim then this is the only way to achieve peace in the Rwenzori. Otherwise the conflict will continue.”